Re: The Sun of the Wind

Posted: Fri May 05, 2017 7:05 pm

Peter Villella, (2014).

The Last Acolhua: Alva Ixtlilxochitl and Elite Native Historiography in Early New Spain.

Colonial Latin American Review, 23(1),

To begin, the legal and political activities of earlier leaders such as don Hernando Pimentel

had resulted in a broad paper trail rich with genealogical and historical information,

and their children were among Alva Ixtlilxochitl's primary informants and collaborators

(Carrasco 1974; O'Gorman 1975, 23, 47–85, 285–87).

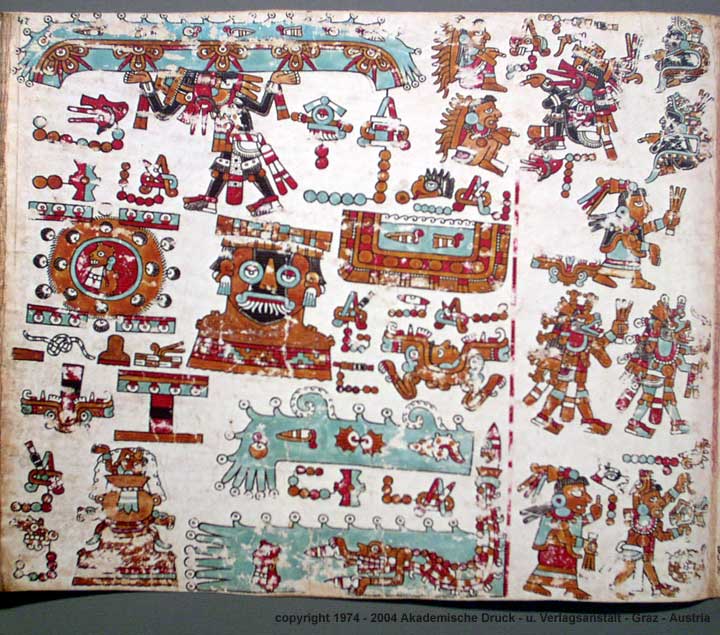

Meanwhile, the chronicler's pictorial sources—which he erroneously believed to be preHispanic—

were also artifacts of post-conquest efforts to defend cacique patrimonies and tribute rights

(Carrera Stampa 1971, 223–33; Romero Galván 2003a; García 2006, 59–61).

Alva Ixtlilxochitl's source materials thus reflected not only a primordial Acolhua knowledge,

but also the postconquest maneuverings of noble families seeking to contest and

reframe ancestral claims in terms admissible to colonial authorities (Douglas 2010, 2001 n17).

Overall, Alva Ixtlilxochitl inherited (or was privy to) at least two discrete ‘archives’ of elite

Acolhua historiography, self-representation, and memory. The first came from Tetzcoco, where

the children and grandchildren of the tlatoani Nezahualpilli (r. 1473–1515) helped pioneer the

post-conquest discourse of cacique rights, arguing that both natural and positive law obliged

Spanish power to respect the suzerainty of native ruling lineages. ...

Alva Ixtlilxochitl's other primary sources of information came from Teotihuacan,

an Acolhua Province previously subject to Tetzcoco,

where his mother retained the local cacicazgo (cacique's entailed estate) (Munch Galindo 1976).

...

The Last Acolhua: Alva Ixtlilxochitl and Elite Native Historiography in Early New Spain.

Colonial Latin American Review, 23(1),

To begin, the legal and political activities of earlier leaders such as don Hernando Pimentel

had resulted in a broad paper trail rich with genealogical and historical information,

and their children were among Alva Ixtlilxochitl's primary informants and collaborators

(Carrasco 1974; O'Gorman 1975, 23, 47–85, 285–87).

Meanwhile, the chronicler's pictorial sources—which he erroneously believed to be preHispanic—

were also artifacts of post-conquest efforts to defend cacique patrimonies and tribute rights

(Carrera Stampa 1971, 223–33; Romero Galván 2003a; García 2006, 59–61).

Alva Ixtlilxochitl's source materials thus reflected not only a primordial Acolhua knowledge,

but also the postconquest maneuverings of noble families seeking to contest and

reframe ancestral claims in terms admissible to colonial authorities (Douglas 2010, 2001 n17).

Overall, Alva Ixtlilxochitl inherited (or was privy to) at least two discrete ‘archives’ of elite

Acolhua historiography, self-representation, and memory. The first came from Tetzcoco, where

the children and grandchildren of the tlatoani Nezahualpilli (r. 1473–1515) helped pioneer the

post-conquest discourse of cacique rights, arguing that both natural and positive law obliged

Spanish power to respect the suzerainty of native ruling lineages. ...

Alva Ixtlilxochitl's other primary sources of information came from Teotihuacan,

an Acolhua Province previously subject to Tetzcoco,

where his mother retained the local cacicazgo (cacique's entailed estate) (Munch Galindo 1976).

...