I am going to explore the hypothesis that Ku-run-ta is related to Karyanda, a city just south of Miletus:

and that it was the source of the ethnonym Carian.

From Wikipedia, so of course it has to be reliable:

"Caria (/ˈkɛəriə/; from Greek: Καρία, Karia, Turkish: Karya) was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid-Ionia (Mycale) south to Lycia and east to Phrygia.[1] The Ionian and Dorian Greeks colonized the west of it and joined the Carian population in forming Greek-dominated states there. The inhabitants of Caria, known as Carians, had arrived there before the Ionian and Dorian Greeks.

They were described by Herodotos as being of Minoan Greek descent,[2] while the Carians themselves maintained that they were Anatolian mainlanders intensely engaged in seafaring and were akin to the Mysians and the Lydians.[2] The Carians did speak an Anatolian language, known as Carian, which does not necessarily reflect their geographic origin, as Anatolian once may have been widespread.[citation needed] Also closely associated with the Carians were the Leleges, which could be an earlier name for Carians or for a people who had preceded them in the region and continued to exist as part of their society in a reputedly second-class status.[citation needed]

Homer's Iliad records that at the time of the Trojan War, the city of Miletus belonged to the Carians, and was allied to the Trojan cause

Herodotus, the famous historian was born in Halicarnassus during the 5th century BC.

According to Herodotos, the legendary King Kar, son of Zeus and Creta, founded Caria and named it after him,

and his brothers Lydos and Mysos founded Lydia and Mysia, respectively.

elsewhere:

"Caria and the Carians are mentioned for the first time in the cuneiform texts of the Old Assyrian and Hittite Empires, i.e., between c.1800 and c.1200.

The country was called Karkissa. [perhaps confused readings of Carcamesh].

The people are absent from the Egyptian texts of this age. [And that is not likely either.]

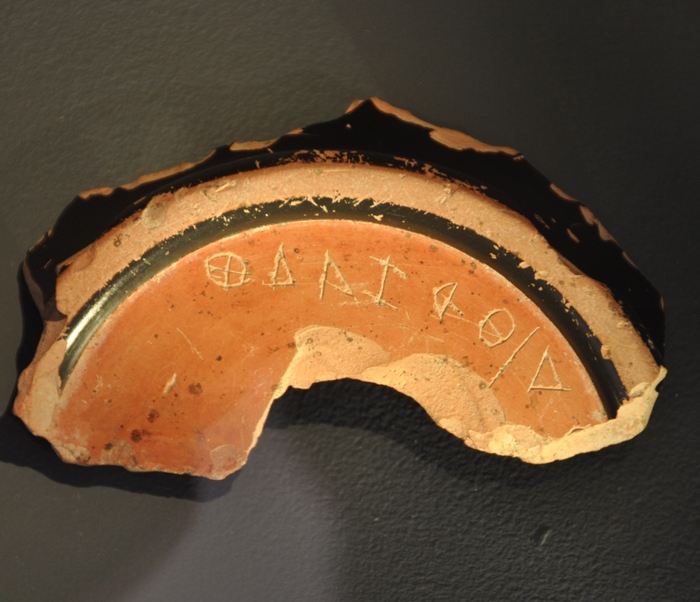

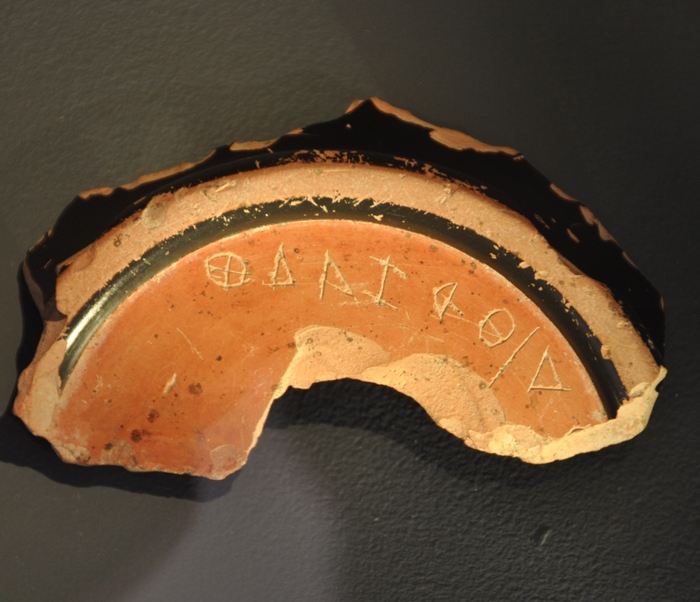

An "incomprehensible" Carian inscription:

After a gap of some four centuries in which they are mentioned only once, the first to mention the Carians was the Greek poet Homer. In the Catalogue of Ships, he tells that they lived in Miletus, on the Mycale peninsula, and along the river Meander. According to Homer, they had sided with the Trojans in the Trojan War[Homer, Iliad 2.867ff.]

elsewhere under Carians:

It is not clear when the Carians enter into history. The definition is dependent on corresponding Caria and the Carians to the "Karkiya" or "Karkisa" mentioned in the Hittite records.

Bronze Age Karkisa are first mentioned as having aided the Assuwa League against the Hittite King Tudhaliya I.

Later in 1323 BC, King Arnuwandas II was able to write to Karkiya for them to provide asylum for the deposed Manapa-Tarhunta of "the land of the Seha River", one of the principalities within the Luwian Arzawa complex in western Anatolia.

This they did, allowing Manapa-Tarhunta to take back his kingdom.

In 1274 BC, Karkisa are also mentioned among those who fought on the Hittite Empire side against the Egyptians in the Battle of Kadesh. Taken as a whole, Hittite records seem to point at a Luwian ancestry for the Carians and, as such, they would have lost their literacy through the Dark Age of Anatolia.

The relationship between the Bronze Age "Karkiya" or "Karkisa" and the Iron Age Caria and the Carians is complicated, despite having western Anatolia as common ground, by the uncertainties regarding the exact location of the former on the map within Hittite geography.[2] Yet, the supposition is suitable from a linguistic point-of-view given that the Phoenicians were calling them "KRK" in their abjad script and they were referred to as "krka" in Old Persian.

The Carians next appear in records of the early centuries of the first millennium BC;

Homer's writing about the golden armour or ornaments of the Carian captain Nastes, the brother of Amphimachus and son of Nomion,[3]

reflects the reputation of Carian wealth that may have preceded the Greek Dark Ages and thus recalled in oral tradition.

[and just for min]

In some translations of Biblical texts, the Carians are mentioned in 2 Kings 11:4, 11:19 (/kɑˈɽi/; כָּרִי, in Hebrew literally "like fat sheep/goat", contextually "noble" or "honored") and perhaps alluded to in 2 Samuel 8:18, 15:18, and 20:23 (/kɽɛˈti/; כְּרֵתִי, probably unrelated due to the "t", may be Cretans).

They are also named as mercenaries in inscriptions found in ancient Egypt and Nubia, dated to the reigns of Psammetichus I and II.

They are sometimes referred to as the "Cari" or "Khari".

Carian remnants have been found in the ancient city of Persepolis or modern Takht-e-Jamshid in Iran.

The Greek historian Herodotus recorded that Carians themselves believed to be aborigines of Caria but they were also, by general consensus of ancient sources, a maritime people before being gradually pushed inland.[4]

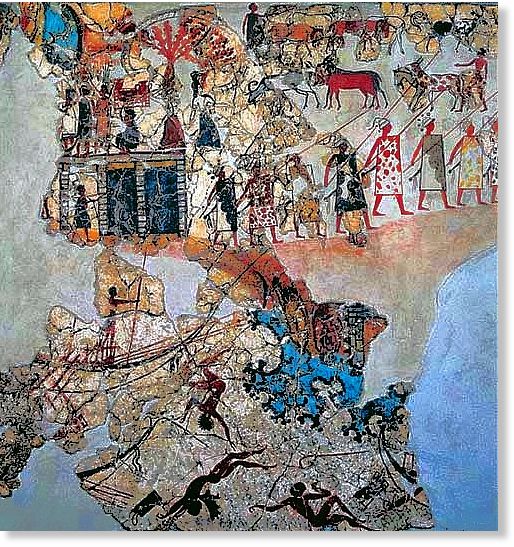

CRESTED HELMETS

Plutarch mentions the Carians as being referred to as "cocks" by the Persians on account of their wearing crests on their helmets;

the epithet was expressed in the form of a Persian privilege when a Carian soldier responsible for killing Cyrus the Younger was rewarded by Artaxerxes II (r. 405/404–359/358 BC) with the honor of leading the Persian army with a golden cock on the point of his spear.[5]

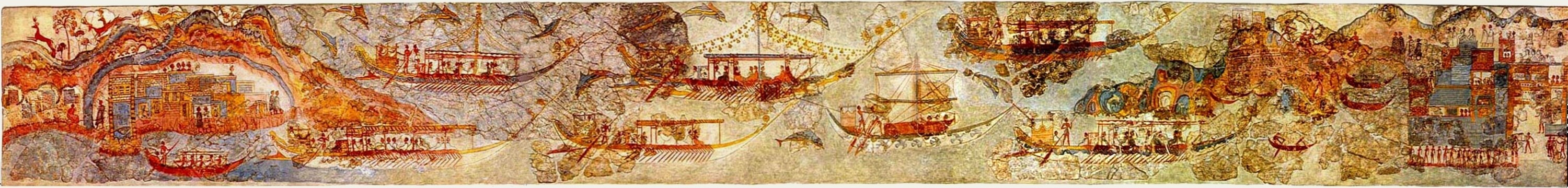

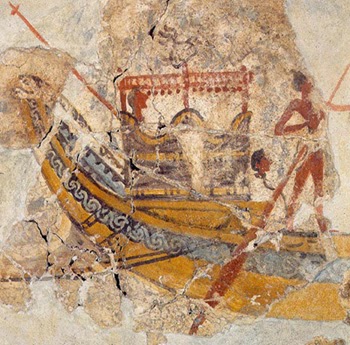

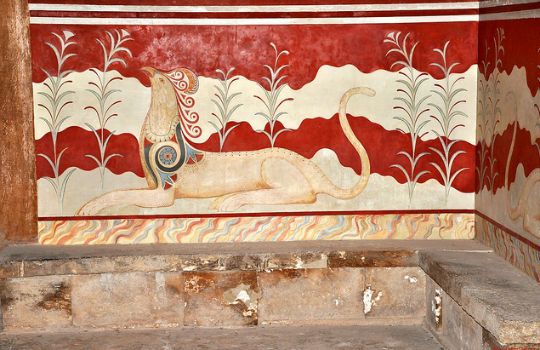

According to Thucydides, it was largely the Carians who settled the Cyclades prior to the Minoans.

The Middle Bronze Age (MMI–MMII) expansion of the Minoans into this region seems to have come at their expense.

Intending to secure revenue in the Cyclades,

Minos of Knossos established a navy with which he established his first colonies by taking control of the Hellenic sea and ruling over the Cyclades islands.

In doing so, Minos expelled the Carians, many of which had turned to piracy as a way of life.

During the Athenian purification of Delos, all graves were exhumed and it was found that more than half were Carians

(identified by style of arms and the method of interment).[6]

According to Strabo, Carians, of all the "barbarians", had a particular tendency to intermingle with the Greeks,

This was particularly the case with the Carians, for, although the other peoples were not yet having very much intercourse with the Greeks nor even trying to live in Hellenic fashion or to learn our language ... yet the Carians roamed throughout the whole of Greece serving on expeditions for pay. ... and when they were driven thence [from the islands] into Asia, even here they were unable to live apart from the Greeks, I mean when the Ionians and Dorians later crossed over to Asia." (Strabo 14.2.28)

Carians and Leleges

The Carians were often linked by Greek writers to the Leleges, but the exact nature of the relationship between Carians and Leleges remains mysterious.

The two groups seem to have been distinct, but later intermingled with each other.

Strabo wrote that they were so intermingled that they were often confounded with each other.[7] However, Athenaeus stated that the Leleges stood in relation to the Carians as the Helots stood to the Lacedaemonians.[8]

This confusion of the two peoples is found also in Herodotus, who wrote that the Carians, when they were allegedly living amid the Cyclades,

were known as Leleges.[9]

Religion

One of the Carian ritual centers was Mylasa, where they worshipped their supreme god, called 'the Carian Zeus' by Herodotus.

Unlike Zeus, this was a warrior god.

It is possible that the goddess Hecate, the patron of pathways and crossroads, originated among the Carians.[12]

Herodotus calls her Athena and says that her priestess would grow a beard when disaster pended.[13]

On Mount Latmos near Miletus, the Carians worshipped Endymion, who was the lover of the Moon and fathered FIFTY children.

[these 50 children were mentioned above, and were likely to be a collection of cities.]

Endymion slept eternally, in the sanctuary devoted to him, which lasted into Roman times.

There is at least one named priestess known to us from this region,

Carminia Ammia who was priestess of Thea Maeter Adrastos and of Aphrodite.

Greek mythology

According to Herodotus, the Carians were named after an eponymous Car, a legendary early king and a brother of Lydus and Mysus, also eponymous founders respectively of Lydians and Mysians and all sons of Atys.[9]

Homer records that Miletus (later an Ionian city),

together with the mountain of Phthries, the river Maeander and the crests of Mount Mycale were held by the Carians at the time of the Trojan War

and that the Carians, qualified by Homer as being of incomprehensible speech, joined the Trojans against the Achaeans under the leadership of Nastes,

brother of Amphimachos ("he who fights both ways") and son of Nomion.

These figures appear only in the Iliad and in a list in Dares of Phrygia's epitome of the Trojan War.

Classical Greeks would often claim that part of Caria to the north was originally colonized by Ionian Greeks before the Dorians.

The Greek goddess Hecate possibly originated among the Carians.[14]

Indeed, most theophoric names invoking Hecate, such as Hecataeus or Hecatomnus, the father of Mausolus, are attested in Caria.[15]

MYSEANS

Their first mention is by Homer, in his list of Trojans allies in the Iliad, and according to whom the Mysians fought in the Trojan War on the side of Troy,

under the command of Chromis and Ennomus the Augur, and were lion-hearted spearmen who fought with their bare hands.[1]

Herodotus in his Histories wrote that the Mysians were brethren of the Carians and the Lydians, originally Lydian colonists in their country, and as such,

they had the right to worship alongside their relative nations in the sanctuary dedicated to the Carian Zeus in Mylasa.[2]

Herodotus also mentions a movement of Mysians and associated peoples from Asia into Europe still earlier than the Trojan War,

wherein the Mysians and Teucrians had crossed the Bosphorus into Europe

and after conquering all of Thrace pressed forward till they came to the Ionian Sea, while southward they reached as far as the river Peneus.[3]

[Nice to see that David Packard, the author of "Minoan Linear A", is still at it:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Packard_H ... _Institute]

LYDIANS

The Homeric name for the Lydians was Μαίονες, cited among the allies of the Trojans during the Trojan War,

and from this name "Maeonia" and "Maeonians" derive and while these Bronze Age terms have sometimes been used as alternatives for Lydia and the Lydians, nuances have also been brought between them.

The first attestation of Lydians by the name of Lydians occurs in Neo-Assyrian sources. The annals of Assurbanipal (mid-7th century BC)refer to the embassy of Gu(g)gu, king of Luddi, to be identified with Gyges, king of the Lydians. [2]

It seems likely that the term "Lydians" came to be used with reference to the inhabitants of Sardis and its vicinity only with the rise of the Mermnad dynasty. [3]

Herodotus states that the Lydians "were the first men whom we know who coined and used gold and silver currency".[4] While this specifically refers to coinage in electrum, some numismatists think that coinage per se arose in Lydia.[5]

According to Ovid's account, Niobe, daughter of Tantalus [Te Hantalishi] and Dione and the sister of Pelops and Broteas, had known Arachne, a Lydian woman, when she was still in Lydia/Maeonia in her father's lands near to Mount Sipylus, These eponymous figures may have corresponded to the obscure ages associated with the semi-legendary dynasty of the Atyads and/or Tantalids, and situated around the time of the emergence of a Lydian nation from their predecessors and/or previous identities as Maeonians and Luvians.

Several accounts on the dynasty of Tylonids succeeding the Atyads and/or Tantalids are available, and once into the last Lydian dynasty of Mermnads, the legendary accounts surrounding Ring of Gyges [this was likely one of the seal rings, examples of which are shown above],

and Gyges's later enthronement to the Lydian throne and foundation of the new dynasty, by replacing the King Kandaules, the last of the Taylanids,

this in alliance with Kandaules's wife who then became his queen, are Lydian stories in the full sense of the term,

as recounted by Herodotus, who himself may have borrowed his passages from Xanthus of Lydia, a Lydian who had reportedly written a history of his country slightly earlier in the same century.

[This Gyges may be related to the Linear B people ke-ke]

Attestations and Etymology

The name of the Lydian king Γύγης is attested many times in Greek transmission.

In addition, the annals of the Assyrian king Assurbanipal, refer several times to Gu(g)gu, king of Luddi, to be identified with Gyges, king of the Lydians. [1]

[just for min]

Many Bible scholars[2] believe that Gyges of Lydia was the Biblical figure of Gog, ruler of Magog,

who is mentioned in the Book of Ezekiel and the Book of Revelation.

This name is probably of Carian origin, being cognate with Hitt. ḫuḫḫa-, Luw. /huha-/ and Lyc. xuga- ‘grandfather’.

The Carian name quq is attested as Γυγος in Greek transmission. [3]

This etymology correlates with the intrusive, probably Carian origin of the Mermnad dynasty in Lydia. [4]

Allegorical accounts of Gyges' rise to power

Authors throughout ancient history have told differing stories of Gyges's rise to power, which considerably vary in detail,

but virtually all involve Gyges seizing the throne, killing King Candaules and marrying Candaules' Queen.

[This last is important in matriarchal societies.]

Gyges was the son of Dascylus.

Dascylus was recalled from banishment in Cappadocia by the Lydian king Candaules and sent his son back to Lydia instead of himself.

According to Nicolaus of Damascus,

Gyges soon became a favourite of Candaules

and was dispatched by him to fetch Tudo, the daughter of Arnossus of Mysia, whom the Lydian king wished to make his queen.

[again, this last is important in matriarchal societies.]

On the way Gyges fell in love with Tudo, who complained to Sadyates of his conduct.

Forewarned that Candaules intended to punish him with death,

Gyges assassinated Candaules in the night and seized the throne.

In his turn, the Lydian king took as his paidika Magnes,

a handsome youth from Smyrna noted for his elegant clothes and fancy korymbos hairstyle which he bound with a golden band.

One day Magnes was singing poetry to the local women,

which outraged their male relatives, who grabbed Magnes, stripped him of his clothes and cut off his hair.[5]

According to Plutarch, Gyges seized power with the help of Arselis of Mylasa, the captain of the Lydian bodyguard, whom he had won over to his cause.

In the account of Herodotus, which may be traced to the poet Archilochus of Paros,

[but probably should not be, as Herodotus was a native of Halicarnasos,

and thoroughly familiar with the Lycian variant of the Epic Cycle}

Gyges was a bodyguard of Candaules, who believed his wife to be the most beautiful woman on Earth.

Candaules insisted upon showing the reluctant Gyges his wife when disrobed as he wanted to show her beauty,

which so enraged her that she gave Gyges the choice of murdering her husband and making himself king,

or of being put to death himself.

Finally, in the more allegorical account of Plato (The Republic, II), a parallel account may be found. Here, Gyges was a shepherd, who discovered a magic ring of invisibility, by means of which he murdered the King and won the affection of the Queen. This account bears marked similarity to that of Herodotus.

[Except that the shepherd finds the ring in a "cave" with a suit of Bronzew Age armor.]

In all cases, civil war ensued on the death of the King,

which was only ended when Gyges sought to justify his ascendance to the throne by petitioning for the approval of the Oracle at Delphi.

According to Herodotus, Gyges plied the Oracle with numerous gifts,

notably six mixing bowls minted of gold extracted from the Pactolus river weighing thirty talents.

The Oracleat Delphi confirmed Gyges as the rightful Lydian King,

gave moral support to the Lydians over the Asian Greeks,

and also claimed that the dynasty of Gyges would be powerful,

but due to his usurpation of the throne would fall in the fifth generation.

This claim was later proven true, though perhaps by the machination of the Oracle's successor:

Gyges's fourth descendant, Croesus, prompted by a prophecy of the later Oracle,

attacked the Persian armies of Cyrus the Great and lost the kingdom as a result.

Reign and death

Once established on the throne, Gyges devoted himself to consolidating his kingdom and making it a military power,

although exactly how far the Lydian kingdom extended under his reign is difficult to ascertain.

He captured Colophon, already largely Lydianized in tastes and customs

and Magnesia on the Maeander, the only other Aeolian colony in the largely Ionian southern Aegean coast of Anatolia,

and probably also Sipylus, whose successor was to become the city also named Magnesia in later records.

Smyrna was besieged[6] and alliances were entered into with Ephesus and Miletus.

To the north, the Troad was brought under Lydian control.

The armies of Gyges pushed back the Cimmerians,

who had ravaged Asia Minor and caused the fall of Phrygia.

During his campaigns against the Cimmerians, an embassy was sent to Assur-bani-pal at Nineveh in the hope of obtaining his help against the Cimmerians.

But the Assyrians were otherwise engaged,

and Gyges turned to Egypt, sending his faithful Carians troops along with Ionian mercenaries to assist Psammetichus in shaking off the Assyrian yoke.

Gyges later fell in a battle against the Cimmerii under Dugdamme

(called Lygdamis by Strabo i. 3. 21—"who probably mistook the Greek Delta Δ for a Lambda Λ"),

who had previously advanced as far as the town of Sardis.

Gyges was succeeded by his son Ardys II.

Several expressions on Lydians were in common use in ancient Greek and in Latin languages,

and a collection and detailed treatment of these were done by Erasmus in his Adagia.