AUSTIN, Texas — C. Andrew Hemmings, research associate of the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory (TARL) at The University of Texas at Austin, will lead an underwater archeological expedition July 30 to Aug. 12 in the Gulf of Mexico to search for submerged evidence of the first Americans.

Hemmings and James Adovasio, director of the Mercyhurst College Archaeological Institute in Erie, Pa., who serves as co-principal investigator of the project, will study ancient submerged coastlines in the northeastern Gulf to determine where early Americans, known as the Clovis culture, might have lived more than 12,000 years ago when the underwater terrain was dry land.

At Least They Are Trying

Moderators: MichelleH, Minimalist, JPeters

-

Minimalist

- Forum Moderator

- Posts: 16046

- Joined: Mon Sep 26, 2005 1:09 pm

- Location: Arizona

At Least They Are Trying

http://www.utexas.edu/news/2008/07/14/tarl_gulf/

Something is wrong here. War, disease, death, destruction, hunger, filth, poverty, torture, crime, corruption, and the Ice Capades. Something is definitely wrong. This is not good work. If this is the best God can do, I am not impressed.

-- George Carlin

-- George Carlin

Spending Money

They either know something we don't know, or they'll have a fun summer sailing around Western Florida before the hurricanes hit.

Natural selection favors the paranoid

-

Minimalist

- Forum Moderator

- Posts: 16046

- Joined: Mon Sep 26, 2005 1:09 pm

- Location: Arizona

I'll certainly buy the idea that they know something we don't.

Something is wrong here. War, disease, death, destruction, hunger, filth, poverty, torture, crime, corruption, and the Ice Capades. Something is definitely wrong. This is not good work. If this is the best God can do, I am not impressed.

-- George Carlin

-- George Carlin

There is a beach area called McFaddins between Port Arthur and High Island that has washed ashore litterly hundreds of Clovis. The Plesticene beach was 50 miles offshore. The early people would take advantage of the seafood, so they would camp what is now far offshore in this currently shallow water. All the early things we are looking for are offshore, not only in the gulf, but the Pacific.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aucilla_River

This would be my best guess. Clovis material is known to

prevail along and in the Aucilla River. Follow the Aucilla

River south to the Pleistocene Coast line and there

should be some heavy midden material out there!

http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/vertpaleo/auci ... lanich.htm

QUATERNARY PERIOD

The Quaternary Period encompasses the last 1.8-million years of geologic history. The Quaternary Period is made of two geologic epochs, the Pleistocene Epoch (1.8 million to 10,000 years ago) and the Holocene Epoch (10,000 years ago to the present) (Figure 2). It was a time of worldwide glaciations, widely fluctuating sea levels, unique animal populations, and the emergence of man. Seas alternately flooded and retreated from the land area of Florida. Most of the landforms characterizing Florida’s modern topography, as well as the springs, lakes and rivers dotting the state today formed during the Quaternary.

The Pleistocene Epoch, also known as "The Ice Age," was punctuated by at least four great glacial periods. During each glaciation, huge ice sheets formed and spread southward out of Canada, covering much of the northern United States. Sea water provided the primary source of water for the expanding glaciers. As the ice sheets enlarged, sea level dropped as much as 400 feet below present level, and the land area of Florida increased dramatically (Figure 16). During peak glacial periods when sea level was lowest, Florida’s Gulf of Mexico coastline was probably situated some 100 miles west of its current position.

The fresh-water table in Florida was probably much lower than today during the Pleistocene sea level low stands. The climate may have been significantly drier as a result. Surface water features such as springs and lakes were less abundant. Only the hardiest of trees, such as oaks, and varieties of ragweed and dry-tolerant grasses would have flourished, giving Pleistocene Florida the appearance of the modern African savannas.

The glaciations were interrupted by warmer interglacial intervals, with Earth’s climate warming considerably. As the climate warmed, the glaciers melted, raising sea level and flooding the Florida peninsula. At the peak interglacial stages, sea level stood at least 100 to 150 feet above the present level, and peninsular Florida probably consisted of islands. Figure 16 illustrates the probable Pleistocene shoreline positions in Florida during the glacial and interglacial periods.

Many of Florida’s modern topographic features and surficial sediments were created or deposited during the various Pleistocene sea level high stands. Waves and currents in these ancient seas eroded the exposed formations of previous epochs, reshaping the earlier landforms and redistributing the eroded sediments over a wide area. At the same time, rivers and longshore currents transported tremendous quantities of sediments into Florida from the coastal plain surrounding the Appalachian Mountains to the north. Much of the quartz sand covering the state today, as well as the heavy mineral deposits, trace their origin to rocks of this once-great mountain chain.

The Pleistocene seas spread a blanket of sand over the limestones underlying Florida’s Gulf coast, infilling the irregular rock surface, forming a relatively featureless sea bottom. During the sea-level high stands, and as the seas retreated, shore waves and near-shore currents eroded a series of relict, coast-parallel scarps and constructed sand ridges spanning the state. Many of these features are formed on or carved out of older geologic landforms and are today stranded many miles inland. Notable examples include the Cody Scarp, Trail Ridge, Brooksville Ridge, and Lake Wales Ridge (Figure 17). Some of the lowland valleys probably evolved largely from dissolution and lowering of the underlying limestones, and these areas may well have functioned as Pleistocene lagoons or waterways bordering the emergent ridges. The Eastern Valley probably contained such a waterway, situated between the relict Atlantic Coastal Ridge on the east and the higher ridges of the central peninsula.

The karst nature of the Eocene, Oligocene, and Miocene limestones comprising the foundation of Florida influenced the development of Pleistocene landforms. For millions of years, naturally acidic rain and ground water flowed through these limestones, dissolving a myriad of conduits and caverns out of the rock. In some cases, the caverns collapsed, forming new sinkholes and modifying the existing landforms through collapse and lowering of the limestone bedrock. In some areas large dissolution valleys formed, such as the Western and Central Valleys of the central peninsula, where dissolution processes lowered the valley floors relative to the surrounding highlands (Figure 17). Many of the larger Pleistocene sinkholes and collapse depressions remain today as lakes dotting the Florida landscape.

The unique geograpic position of southernmost Florida during the Pleistocene produced a terrain significantly different from the rest of the peninsula. Here, carbonate sediments predominate, and the sandy ridges of the central peninsula are absent. South of approximately Palm Beach, the marine continental slope approaches the edge of the Florida peninsula. Most of the continental quartz sands, moving southward with the coastal currents during the Pleistocene, were funneled offshore and lost down the continental slope. As the glaciers melted and sea level rose, nutrient-rich water flooded the southern tip of Florida. Calcium carbonate, in the form of broken shell fragments and chemically-precipitated particles, was the main source of sediments.

The area of modern-day Everglades was a shallow marine bank, similar to the present Bahama Banks. Carbonate sediment bars, some vegetated by mangrove trees, protected the eastern edge of the bank near Miami and to the south along the lower Florida Keys. Calcareous sediments and bryozoan reefs accumulated on the shallow bank under low wave energy conditions. These sediments compacted and eventually solidified to form the limestone that floors the Everglades today. Dissolution and cementation by rainwater and acidic organics has since produced the Everglade’s jagged, craggy rock surface. As sea level climbed to its present level in the Late Pleistocene and throughout the Holocene, modern surface-water drainage patterns formed, ultimately providing water for the immense, southward-flowing "river of grass" which would become the Everglades.

Florida Bay, stranded as dry land during glacial periods, was most likely a Pleistocene lagoon during high stands of sea level. It was protected from extensive wave activity on the south by a chain of the then-living coral reefs of the Florida Keys. Because of the protected, low-energy nature of the south Florida area during the high Pleistocene seas, relict wave-formed features such as bars, spits and beach ridges are rare.

Near the southern rim of the Florida Platform’s escarpment lies a fringeline of living and dead coral reefs (Figure 11). The dead coral reefs form the islands of the Florida Keys. The edge of the Florida Platform, marked by the 300-feet depth contour line, lies four-to-eight miles south of the Keys. Today, living coral reefs grow in the shallow waters seaward of the Keys. This environment is ideal for the growth of coral: a shallow-water shelf, subtropical latitude and the warm, nutrient-rich Gulf Stream nearby.

The geological history of the Florida Keys began about 1.8 million years ago, when a shallow sea covered what is now south Florida. From that time to about 10,000 years ago, often called the Pleistocene "Ice Ages," world sea levels underwent many fluctuations of several hundred feet, both above and below present sea level, in response to the repeated growth and melting of the great glaciers. Colonies of coral became established in the shallow sea along the rim of the broad, flat Florida Platform. The subtropical climate allowed the corals to grow rapidly and in great abundance, forming reefs. As sea levels fluctuated, the corals maintained footholds along the edge of the platform; their reefs grew upward when sea level rose, and their colonies retreated to lower depths along the platform’s rim when sea levels fell. During times of rising sea levels, dead reefs provided good foundations for new coral growth. In this manner, during successive phases of growth, the Key Largo Limestone accumulated from 75 to 200-feet thick in places. The Key Largo Limestone is a white-to-tan limestone that is primarily the skeletal remains of corals, with invertebrate shells, marine plant and algal debris and lime-sand. The last major drop in sea level exposed the ancient reefs, which are the present Keys. Exposures of the Key Largo Limestone can be seen in many places along the Keys: in canal cuts, at shorelines, and in construction spoil piles.

During reef growth, carbonate sand banks periodically accumulated behind the reef in environments similar to the Bahamas today. One such lime-sand bank covered the southwestern end of the coral reefs and, when sea level last dropped, the exposed lime-sand or oöid bank formed the Lower Keys. This white-to-light tan, granular rock, the Miami Limestone, is composed of tiny, spherical oöliths, lime-sand and shells. Oöliths may be up to 2 millimeters in diameter and are made of concentric layers of calcium carbonate deposited around a nucleus of sand, shell, or other foreign matter. Throughout the Lower Keys, the Miami Limestone lies on top of the coralline Key Largo Limestone, and varies from a few feet up to 35 feet in thickness. The northwest-southeast aligned channels between islands of the Lower Keys were cut in the broad, soft, oölite bank by tidal currents. Then, as today, the tidal currents flowed rapidly into and out of the shallow bay behind the reefs, keeping the channels scoured clean.

CHAPTER 4

GEOLOGY and MAN

Frank R. Rupert P.G. 149 and Kenneth M. Campbell P.G. 192

EARLY MAN AND HIS ENVIRONMENT

The Holocene Epoch began 10,000 years ago during a slow warming of the Earth’s climate. Sea level climbed intermittently toward its present level from a glacial low about 8,000 years ago. As the encroaching sea shrank the state to its present size, paleo-Indians spread throughout Florida, flourishing on the abundant resources. The first paleo-Indians probably migrated into the state from the continental mainland between 10,000 and 12,000 years ago. The earliest documentation of man’s presence in Florida comes from Little Salt Spring in Sarasota County. Paleo-Indian skeletal remains from this site have been dated at over 10,000 years old.

Sea level then was as much as 100 feet lower than at present, and the land area of Florida was much larger than it is n

During the paleo-Indian period (14,000 - 8,500 BP) and the Archaic period (8,500 - 3,000 BP) which followed, exploitation of the geologic resources of Florida was probably limited to the use of caves and sinks as water sources and possible shelter, and outcrops of chert for the production of projectile points, scrapers and other lithic tools. The next major advancement in the utilization of geologic resources was the manufacture of fired clay pottery. The earliest examples of pottery appear at various places in the state between 3,000 - 4,000 BP. The use of clay or mud to seal vertical post-walled structures and the use of sandstone scrapers has also been documented.

Throughout much of the Neogene and Pleistocene, Florida was home to a diverse animal population (Figure 18, Figure 19, Figure 20, and Figure 21). Many unique and now-extinct species migrated into temperate Florida to escape the cold and ice of the huge glaciers to the north. Fossil remains found today in Neogene and Pleistocene deposits include mastodons, mammoths, black bears, giant sloths, capybaras, beavers, lemmings, dire wolves, horses, tapirs, camels, glyptodonts, llamas and saber-toothed cats. Florida may have been a final refuge for many species as extinction took its toll on the once-diverse animal populations. Animals such as the mastodon, mammoth, giant sloth, and saber-toothed cat disappeared forever.

th the rising sea level during the Holocene came a corresponding rise in the state’s ground-water table. Most of Florida’s springs, lakes, and spring-fed river systems developed during the Holocene Epoch. The rate of sea level rise slowed about 3,500 years ago when sea level was five feet below present level. By that time the beaches, barrier islands, and spits characterizing Florida’s modern coastline had evolved. The complex geologic processes which shaped Florida into its present form continue today. Florida continues to evolve as the sea shapes the coasts and redistributes the sands and other sediments which are to be the rocks of future epochs.

Here ya go .... Florida's Middle Ground area

http://www.bio.fsu.edu/coleman_lab/flor ... e_grounds/

This would be my best guess. Clovis material is known to

prevail along and in the Aucilla River. Follow the Aucilla

River south to the Pleistocene Coast line and there

should be some heavy midden material out there!

http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/vertpaleo/auci ... lanich.htm

QUATERNARY PERIOD

The Quaternary Period encompasses the last 1.8-million years of geologic history. The Quaternary Period is made of two geologic epochs, the Pleistocene Epoch (1.8 million to 10,000 years ago) and the Holocene Epoch (10,000 years ago to the present) (Figure 2). It was a time of worldwide glaciations, widely fluctuating sea levels, unique animal populations, and the emergence of man. Seas alternately flooded and retreated from the land area of Florida. Most of the landforms characterizing Florida’s modern topography, as well as the springs, lakes and rivers dotting the state today formed during the Quaternary.

The Pleistocene Epoch, also known as "The Ice Age," was punctuated by at least four great glacial periods. During each glaciation, huge ice sheets formed and spread southward out of Canada, covering much of the northern United States. Sea water provided the primary source of water for the expanding glaciers. As the ice sheets enlarged, sea level dropped as much as 400 feet below present level, and the land area of Florida increased dramatically (Figure 16). During peak glacial periods when sea level was lowest, Florida’s Gulf of Mexico coastline was probably situated some 100 miles west of its current position.

The fresh-water table in Florida was probably much lower than today during the Pleistocene sea level low stands. The climate may have been significantly drier as a result. Surface water features such as springs and lakes were less abundant. Only the hardiest of trees, such as oaks, and varieties of ragweed and dry-tolerant grasses would have flourished, giving Pleistocene Florida the appearance of the modern African savannas.

The glaciations were interrupted by warmer interglacial intervals, with Earth’s climate warming considerably. As the climate warmed, the glaciers melted, raising sea level and flooding the Florida peninsula. At the peak interglacial stages, sea level stood at least 100 to 150 feet above the present level, and peninsular Florida probably consisted of islands. Figure 16 illustrates the probable Pleistocene shoreline positions in Florida during the glacial and interglacial periods.

Many of Florida’s modern topographic features and surficial sediments were created or deposited during the various Pleistocene sea level high stands. Waves and currents in these ancient seas eroded the exposed formations of previous epochs, reshaping the earlier landforms and redistributing the eroded sediments over a wide area. At the same time, rivers and longshore currents transported tremendous quantities of sediments into Florida from the coastal plain surrounding the Appalachian Mountains to the north. Much of the quartz sand covering the state today, as well as the heavy mineral deposits, trace their origin to rocks of this once-great mountain chain.

The Pleistocene seas spread a blanket of sand over the limestones underlying Florida’s Gulf coast, infilling the irregular rock surface, forming a relatively featureless sea bottom. During the sea-level high stands, and as the seas retreated, shore waves and near-shore currents eroded a series of relict, coast-parallel scarps and constructed sand ridges spanning the state. Many of these features are formed on or carved out of older geologic landforms and are today stranded many miles inland. Notable examples include the Cody Scarp, Trail Ridge, Brooksville Ridge, and Lake Wales Ridge (Figure 17). Some of the lowland valleys probably evolved largely from dissolution and lowering of the underlying limestones, and these areas may well have functioned as Pleistocene lagoons or waterways bordering the emergent ridges. The Eastern Valley probably contained such a waterway, situated between the relict Atlantic Coastal Ridge on the east and the higher ridges of the central peninsula.

The karst nature of the Eocene, Oligocene, and Miocene limestones comprising the foundation of Florida influenced the development of Pleistocene landforms. For millions of years, naturally acidic rain and ground water flowed through these limestones, dissolving a myriad of conduits and caverns out of the rock. In some cases, the caverns collapsed, forming new sinkholes and modifying the existing landforms through collapse and lowering of the limestone bedrock. In some areas large dissolution valleys formed, such as the Western and Central Valleys of the central peninsula, where dissolution processes lowered the valley floors relative to the surrounding highlands (Figure 17). Many of the larger Pleistocene sinkholes and collapse depressions remain today as lakes dotting the Florida landscape.

The unique geograpic position of southernmost Florida during the Pleistocene produced a terrain significantly different from the rest of the peninsula. Here, carbonate sediments predominate, and the sandy ridges of the central peninsula are absent. South of approximately Palm Beach, the marine continental slope approaches the edge of the Florida peninsula. Most of the continental quartz sands, moving southward with the coastal currents during the Pleistocene, were funneled offshore and lost down the continental slope. As the glaciers melted and sea level rose, nutrient-rich water flooded the southern tip of Florida. Calcium carbonate, in the form of broken shell fragments and chemically-precipitated particles, was the main source of sediments.

The area of modern-day Everglades was a shallow marine bank, similar to the present Bahama Banks. Carbonate sediment bars, some vegetated by mangrove trees, protected the eastern edge of the bank near Miami and to the south along the lower Florida Keys. Calcareous sediments and bryozoan reefs accumulated on the shallow bank under low wave energy conditions. These sediments compacted and eventually solidified to form the limestone that floors the Everglades today. Dissolution and cementation by rainwater and acidic organics has since produced the Everglade’s jagged, craggy rock surface. As sea level climbed to its present level in the Late Pleistocene and throughout the Holocene, modern surface-water drainage patterns formed, ultimately providing water for the immense, southward-flowing "river of grass" which would become the Everglades.

Florida Bay, stranded as dry land during glacial periods, was most likely a Pleistocene lagoon during high stands of sea level. It was protected from extensive wave activity on the south by a chain of the then-living coral reefs of the Florida Keys. Because of the protected, low-energy nature of the south Florida area during the high Pleistocene seas, relict wave-formed features such as bars, spits and beach ridges are rare.

Near the southern rim of the Florida Platform’s escarpment lies a fringeline of living and dead coral reefs (Figure 11). The dead coral reefs form the islands of the Florida Keys. The edge of the Florida Platform, marked by the 300-feet depth contour line, lies four-to-eight miles south of the Keys. Today, living coral reefs grow in the shallow waters seaward of the Keys. This environment is ideal for the growth of coral: a shallow-water shelf, subtropical latitude and the warm, nutrient-rich Gulf Stream nearby.

The geological history of the Florida Keys began about 1.8 million years ago, when a shallow sea covered what is now south Florida. From that time to about 10,000 years ago, often called the Pleistocene "Ice Ages," world sea levels underwent many fluctuations of several hundred feet, both above and below present sea level, in response to the repeated growth and melting of the great glaciers. Colonies of coral became established in the shallow sea along the rim of the broad, flat Florida Platform. The subtropical climate allowed the corals to grow rapidly and in great abundance, forming reefs. As sea levels fluctuated, the corals maintained footholds along the edge of the platform; their reefs grew upward when sea level rose, and their colonies retreated to lower depths along the platform’s rim when sea levels fell. During times of rising sea levels, dead reefs provided good foundations for new coral growth. In this manner, during successive phases of growth, the Key Largo Limestone accumulated from 75 to 200-feet thick in places. The Key Largo Limestone is a white-to-tan limestone that is primarily the skeletal remains of corals, with invertebrate shells, marine plant and algal debris and lime-sand. The last major drop in sea level exposed the ancient reefs, which are the present Keys. Exposures of the Key Largo Limestone can be seen in many places along the Keys: in canal cuts, at shorelines, and in construction spoil piles.

During reef growth, carbonate sand banks periodically accumulated behind the reef in environments similar to the Bahamas today. One such lime-sand bank covered the southwestern end of the coral reefs and, when sea level last dropped, the exposed lime-sand or oöid bank formed the Lower Keys. This white-to-light tan, granular rock, the Miami Limestone, is composed of tiny, spherical oöliths, lime-sand and shells. Oöliths may be up to 2 millimeters in diameter and are made of concentric layers of calcium carbonate deposited around a nucleus of sand, shell, or other foreign matter. Throughout the Lower Keys, the Miami Limestone lies on top of the coralline Key Largo Limestone, and varies from a few feet up to 35 feet in thickness. The northwest-southeast aligned channels between islands of the Lower Keys were cut in the broad, soft, oölite bank by tidal currents. Then, as today, the tidal currents flowed rapidly into and out of the shallow bay behind the reefs, keeping the channels scoured clean.

CHAPTER 4

GEOLOGY and MAN

Frank R. Rupert P.G. 149 and Kenneth M. Campbell P.G. 192

EARLY MAN AND HIS ENVIRONMENT

The Holocene Epoch began 10,000 years ago during a slow warming of the Earth’s climate. Sea level climbed intermittently toward its present level from a glacial low about 8,000 years ago. As the encroaching sea shrank the state to its present size, paleo-Indians spread throughout Florida, flourishing on the abundant resources. The first paleo-Indians probably migrated into the state from the continental mainland between 10,000 and 12,000 years ago. The earliest documentation of man’s presence in Florida comes from Little Salt Spring in Sarasota County. Paleo-Indian skeletal remains from this site have been dated at over 10,000 years old.

Sea level then was as much as 100 feet lower than at present, and the land area of Florida was much larger than it is n

During the paleo-Indian period (14,000 - 8,500 BP) and the Archaic period (8,500 - 3,000 BP) which followed, exploitation of the geologic resources of Florida was probably limited to the use of caves and sinks as water sources and possible shelter, and outcrops of chert for the production of projectile points, scrapers and other lithic tools. The next major advancement in the utilization of geologic resources was the manufacture of fired clay pottery. The earliest examples of pottery appear at various places in the state between 3,000 - 4,000 BP. The use of clay or mud to seal vertical post-walled structures and the use of sandstone scrapers has also been documented.

Throughout much of the Neogene and Pleistocene, Florida was home to a diverse animal population (Figure 18, Figure 19, Figure 20, and Figure 21). Many unique and now-extinct species migrated into temperate Florida to escape the cold and ice of the huge glaciers to the north. Fossil remains found today in Neogene and Pleistocene deposits include mastodons, mammoths, black bears, giant sloths, capybaras, beavers, lemmings, dire wolves, horses, tapirs, camels, glyptodonts, llamas and saber-toothed cats. Florida may have been a final refuge for many species as extinction took its toll on the once-diverse animal populations. Animals such as the mastodon, mammoth, giant sloth, and saber-toothed cat disappeared forever.

th the rising sea level during the Holocene came a corresponding rise in the state’s ground-water table. Most of Florida’s springs, lakes, and spring-fed river systems developed during the Holocene Epoch. The rate of sea level rise slowed about 3,500 years ago when sea level was five feet below present level. By that time the beaches, barrier islands, and spits characterizing Florida’s modern coastline had evolved. The complex geologic processes which shaped Florida into its present form continue today. Florida continues to evolve as the sea shapes the coasts and redistributes the sands and other sediments which are to be the rocks of future epochs.

Here ya go .... Florida's Middle Ground area

http://www.bio.fsu.edu/coleman_lab/flor ... e_grounds/

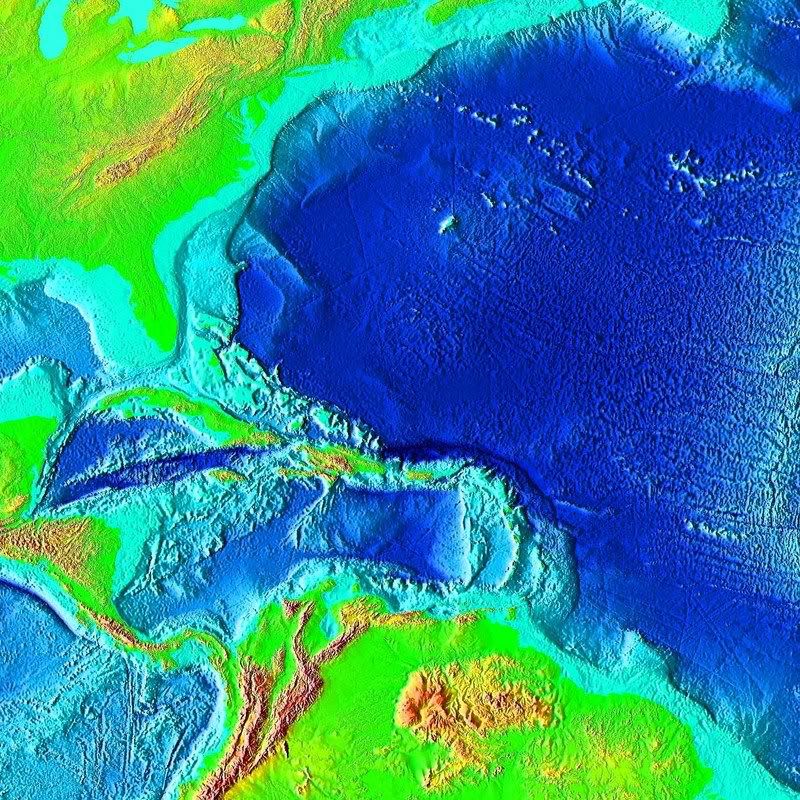

Pleistocene Florida

Well then, that would be a great place to look for a marine settlement. Dropping the shoreline by 120 meters (about 400 feet) off Western Florida provides a tremendously different map of the area when the Bahamas are taken into consideration - it must have been a marine paradise with food readily available.There is a beach area called McFaddins between Port Arthur and High Island that has washed ashore litterly hundreds of Clovis. The Pleistocene beach was 50 miles offshore. The early people would take advantage of the seafood, so they would camp what is now far offshore in this currently shallow water.

Not necessarily on the Pacific side since it does not have the continental shelf that the Atlantic does. I work on a site on an ancient lakebed that has been dated to 18-20kya and it's about 100 miles inland - lots and lots of paleo tools. The lake was a watering spot for many critters.All the early things we are looking for are offshore, not only in the gulf, but the Pacific.

Natural selection favors the paranoid

Pedra Furada

Just take small boats for island hopping and follow the marine food. As gunny inferred, it was probably a helluva lot safer living on islands as opposed to the mainland - fewer predators - dyers wolves, sabers, etc.

Natural selection favors the paranoid

-

Knuckle sandwhich

- Posts: 36

- Joined: Mon Jul 07, 2008 11:50 pm

Marine Food

Hunting animals on island archipelagos typically tips the predator vs prey ecological balance quickly, thereby exterminating the species. It is very difficult to do the same with marine.Why marine?

Flora-wise, if you can live off coconuts and bananas while collecting enough rain water, great.

Natural selection favors the paranoid

Two things from todays news page.

A nice map of where they plan to dive, and a story of a 6000 year old knife found in a Tampa park.

http://www.pittsburghlive.com/images/vi ... -07-15.pdf

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/25692018/

It must have been a nice place to live.

A nice map of where they plan to dive, and a story of a 6000 year old knife found in a Tampa park.

http://www.pittsburghlive.com/images/vi ... -07-15.pdf

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/25692018/

It must have been a nice place to live.

-

Minimalist

- Forum Moderator

- Posts: 16046

- Joined: Mon Sep 26, 2005 1:09 pm

- Location: Arizona

Knuckle sandwhich wrote:Why marine?

Also a tremendous protein source. It's not just the fish, it's the mammals and shellfish, too.

Something is wrong here. War, disease, death, destruction, hunger, filth, poverty, torture, crime, corruption, and the Ice Capades. Something is definitely wrong. This is not good work. If this is the best God can do, I am not impressed.

-- George Carlin

-- George Carlin

-

Knuckle sandwhich

- Posts: 36

- Joined: Mon Jul 07, 2008 11:50 pm

There's something you guys may find interesting when considering early hunter/gatherers in low population settings of high terrestrial animal biomass. It's called Optimal Foraging and deals with the transfer of energy from prey to predator, and how the net energy is maximized by predators. It addresses why hunter/gatherers do not become marine adapted in such settings, and why marine adaption is a very costly compromise in the face of considerably more environmental stress.

Check it out, it may alter your opinion on some matters.

Check it out, it may alter your opinion on some matters.

Heavens to Mergetroid!